Since the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898, the Ahtna have had to compete for the food that has sustained them for over a millennium. After World War II, this competition intensified. In 1946, 9,000 resident hunting licenses were sold; in 1955/56 the number was 31,500. Highways built during World War II provided easy access to the Copper River Basin, so that between 1960 and 1970, the number of salmon fishing permits issued for the upper Copper River subsistence fishery increased 96 percent.

Faced with such unprecedented growth, state managers imposed restrictions on salmon fishing in the upper Copper River. In 1964, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) closed all tributaries of the Copper River and the main channel of the river above the Slana River to subsistence fishing, thus eliminating traditional Ahtna fishing sites on the Tonsina, Klutina and Slana Rivers. This was all done without consulting the Ahtna.

In June of 1964, Markle Ewan, Sr. told Ralph Pirtle, the state management biologist, that he did not agree with the regulations that placed seasonal limits on subsistence harvests. Markle wrote:

“The majority of our Indian people don’t have deep freezers, therefore our main dependable storage food is dried, smoked, salted and canned fish. Believe it or not – one person can eat as much as two fish a day whether fresh or otherwise. So please permit us to get as much fish as we need.

As you know, we don’t take or waste any fish or game like so many sport fishermen and hunters do. We are God abiding citizen people. I don’t believe the whole Copper River tribe will get as much fish in a whole season in the Copper River area as the commercial fishermen would get in one day.”

(Markle Ewan. Sr., 1964 ADF&G Glennallen)

To control further growth of the fishery, state managers, in the summer of 1966, ordered that the Ahtna upriver subsistence fishery open on June 15th instead of June 1st. The Ahtna rejected the state’s assessment of the problem and the method by which the new restriction was imposed.

The Ahtna appealed for statewide support, declaring that they will fish on June 1st “as they have done for centuries” and threatening that “if necessary, each Indian will catch a fish and turn it into the Department of Fish and Game, demanding to be arrested.” Facing organized protest, the state retreated and opened the subsistence fishery on June 1st.

In an article covering the story, the Tundra Times compared the Ahtna’s action to the mass civil disobedience of Barrow people who opposed the ban on spring waterfowl hunting by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. These actions by Inupiat and Ahtna were part of the larger fabric of Native protest that led to the signing of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in December 1971.

Following the passage of ANCSA the U.S. Congress directed the state and federal governments to provide for Alaska Native subsistence rights. The state, responding to the increased pressures on wildlife resources brought about by the oil boom, began to recognize the special claims of subsistence users. In 1978, the Alaska State legislature passed the first comprehensive subsistence law, which gave priority to subsistence, but it did not address the issue of who was a subsistence user.

That same year the Ahtna and ADF&G again clashed over closures to the salmon fishery. To protect the salmon runs, ADF&G closed the upper Copper River subsistence fishery during the week and allowed fishing only on weekends. ADF&G reasoned that more fish were caught during the week (on Tuesdays and Thursdays) than on weekends, and it was better for the fishery if the closure occurred during the week.

The Copper River Native Association (CRNA) objected to the weekday closures, saying it favored non-basin residents over basin residents. At a meeting of the fish and game local advisory committee, 92 people attended including three staff members of the ADF&G who expressed the view it was important to limit the number of fish harvested and the Alaska State Constitution guaranteed equal access.

Tuzzy Consortium Library of Barrow Alaska.

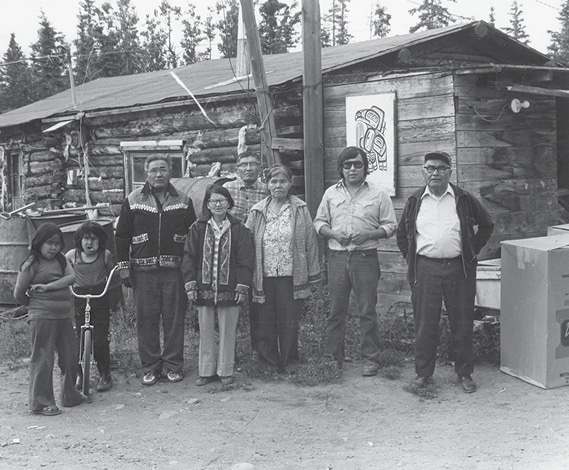

It had been a long, cold winter in the Ahtna region and jobs were scarce. Ahtna Elders Annie Ewan, Martha Jackson, Nancy George and Mary Jackson, known as the “Copper River Four,” were stopped from fishing that summer when state officials padlocked their fishwheels. The Elders were cited by state protection officers for allegedly defying an emergency closure by attempting to fish during the week and they were threatened with prosecution.

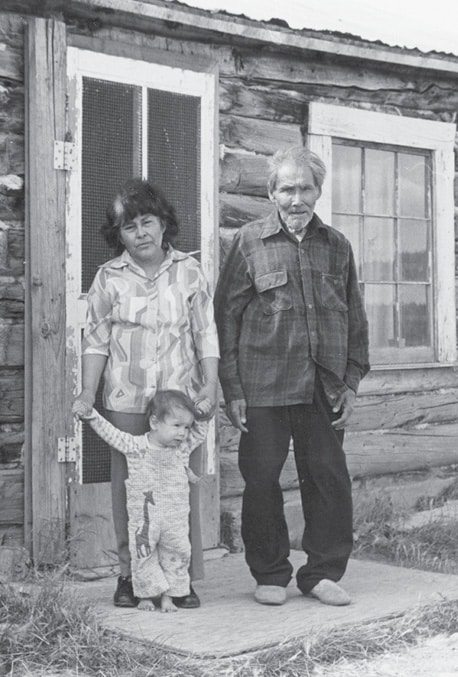

It had been two weeks since the closure and the late Ahtna Elder Annie Ewan (Udzisyu – Caribou clan), had enough and wasn’t going to stand for it. When the ADF&G Commissioner and a State Trooper put a padlock on her fishwheel and told her she would have to stop fishing, she grabbed her bear hunting rifle, a .30-06. She was a petite woman at only 4 feet 10 inches tall, but used her sharpshooting skills to shoot the padlock right off her fishwheel.

Annie’s husband, Pete Ewan, served as the spokesperson for the Elder defendants when they went to court. Pete wholeheartedly believed in complete sovereignty for all Ahtna Athabascans. Ahtna people traveled from all over, like Cantwell and Fairbanks, to show their support. The case against the Elders ended up being dismissed.

Annie and Pete’s daughter, Faye Ewan, was in her mid-twenties during this time and says she remembers it well. She recalls that the Ahtna people had lost thirteen people in the three months leading up to the fishwheels being chained and locked in July. Being cut off from fishing during the peak of the salmon run was upsetting to her parents. They were concerned that they wouldn’t be able to get enough fish in for the winter and for the potlatches. Faye said her parents always said, “It’s our land. We don’t claim it because it belongs to everyone.”

Robert Marshall, president of CRNA, speaking for the majority of Ahtna, said that he did not like the way the new closures were implemented. Ahtna Elders ranging in age from 79 to 94 years had their fish wheels locked up. He further noted that,

“Indians need fish to survive, the older people cannot survive without fish through the winter! Indian people did not come right out and say but they are actually begging to be able to catch fish.”

(Robert Marshall, ADF&G 1978, minutes of the Copper River Advisory Committee, ADF&G Glennallen)

Pete Ewan was interviewed by the Tundra Times the summer following the fishwheels being padlocked. “We know our river fish from our history, long ago in the old days,” he said. He explained that state managers of the resource ignore the Elders’ local knowledge of salmon, and that Athabascan Elders can contribute much to the management of fish. “Every river fish, we know where they go. Down below, when they start monkeying around, the fish don’t come any more.”

Bacille Jackson presented a paper in which he outlined a history of the situation from the Ahtna perspective. In one lifetime, Jackson wrote, the Ahtna had gone from owning all of the land and resources to having to ask permission to hunt and fish in their own homeland.

The Ahtna, he said, had always shared their food and their land, but they had not given up their right to hunt and fish for their livelihood. In fact, he said, they would be stupid to “give up the lifeline of our people throughout history.”

“When our fathers and grandfathers met the first White people to come up the Copper River, there was no question in anyone’s mind that they owned all the land and resources in the area. This included the big game in the hills as well as the fish in the river.

History shows that we were are not greedy with our resources, but shared them first with the Russians, later with the gold miners of 1898, and until this day with the White people who are our neighbors. Furs, big game, timber, minerals, and fish that originally belonged to us have been taken continuously by others with seldom a complaint on our part.

Today we all know times have changed, statehood and the Native land claims bill [ANCSA] seem to bear this out that much of the land doesn’t belong to us anymore. In the few short years since the turn of the century (which many of our old folks can remember) we have come from complete ownership of land and all its riches to what often seems to us at most as trespassers on another’s (sic) land. Now we are told much of the land belongs to others, we are told when to hunt, where to hunt, where to mine, where to cut timbers, when to fish, where to fish, when to trap, where to trap, and on and on and on.

At no time since our fathers completely owned this land have they or we given up our right to live a subsistence lifestyle. We have not traded off the right to catch fish for our families from our river. We are not about to give this right to the State of Alaska or the federal government today or at any future time at any price.

Today we are here to protest what we believe is a great injustice (sic) to our people. We are being told that the fish of the Copper River no longer belong to us and, that we no longer have the right to take them when and how we want for our own needs. Great emphasis seems to be given to the use of the fish by the commercial fishermen in the Cordova area and by the dipnetters from the Fairbanks and Anchorage areas. We seem to be the last people whose need and desires are being met.

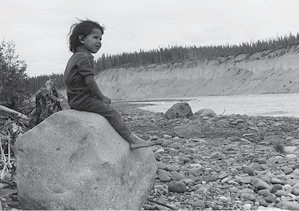

A history of our people show that when fish runs are good, our fathers did well, when fish runs were poor, our people starved. Truly the fish of the Copper River have been the basic necessity for the existence of our people throughout time.

Many of us here today grew up in the 1920s and 1930s when a subsistence lifestyle was necessary. We still hang on to some of that lifestyle. Certainly we would not be too intelligent to give up our right to the lifeline of our people throughout history, on the chance that Alaska and America will never again face depression or wars, and we won’t ever again have to depend on the salmon of the Copper River for our livelihood.

We believe that the State of Alaska doesn’t have the right to lock up our fish wheels or our people for fishing. We further believe the state does not have the right to keep our people from subsistence fishing!

(Bacille Jackson, ADF&G 1978, minutes of the Copper River Advisory Committee, ADF&G Glennallen)

Over forty years have passed since the Copper River Four were issued citations, but the Ahtna people’s fight for the right to fish and hunt on our lands continues to this day.

Historical information for this article was taken from the Ahtna History Book, Ahtna: The People and Their History (www.ahtna.com/book)