Excerpt from the Ahtna History Book, by Simeone, William E., Ph.D.: www.ahtna.com/book.

The potlatch is an important part of Ahtna culture and tradition. It is the most visible or outward expression of Ahtna values. The potlatch is an exchange of gifts and services between two different clans. It is not an exchange between individuals. It is an anchor to the past. As Roy Ewan said,

We were taught to carry on the tradition of honoring our ancestors. We were taught it was important that we do this. Others thought more highly of you if you carried on our culture and tradition. The Bible says to honor thy father and thy mother.

– Roy S. Ewan, 9.21.2016, recorded by Bill Simeone

In the past, the corpse was cremated. Martha and Arthur Jackson explained that as soon as a man died, or was killed in battle, he was cremated. The Jacksons did not know when people began to bury the corpse. They also said that in the past graves were grouped according to relation [clan] but that now they are all mixed up (Martha and Arthur Jackson, 7.3.1968 del/mc).

Long time ago potlatch was not like now, just quiet [now]. Used to be all active, talking. I remember singing. We’re losing that too. Nobody sing much in potlatch now. Just a few people is around now that can sing Indian song dance song. This is getting bad.

– Virginia Pete

When a person died, it was the responsibility of the non-relatives, typically members of the opposite moiety, to dress and dispose of the corpse while the relatives of the deceased mourned. After the body was disposed of, either through cremation or burial, the deceased’s relatives held a potlatch in which they distributed food and gifts to members of the opposite clan, and especially to those people who had taken an active part in the burial of the corpse. If the deceased’s relatives could afford it, they held another potlatch a year or more later in memory of the dead. The potlatch was not only a religious ceremony, but also an important vehicle for gaining personal prestige. It was one way for young men to publicly prove their worth.

Death brings uncertainty, danger, and sorrow. Uncertainty exists especially if the deceased is a community leader. Danger exists in the fear that the deceased’s ghost or spirit may linger and attempt to take the spirit of another person, especially a close relative. To avoid this, members of the opposite side or moiety, preferably a brother-in-law or sister-in-law, takes care of the corpse and digs the grave. Traditionally, those who handled the corpse had to stay home for 10 days, eat alone, and not eat fresh meat. They took a sweat bath and put on new clothes provided by relatives of the deceased. For 30 days, a relative threw bits of food into a fire to feed the deceased’s spirit.

A person’s death also brings sorrow and grief. Glenda Ewan explained that when someone dies those who are grieving have to let the “feeling come out of you.” If you don’t do the right thing by your loved ones, she said “something bother you all the time.”

A lot of people don’t do it all the time, but most of the village thinks when our loved one is gone we have to make what we call a potlatch. By bringing friends together, that makes the feelings come out of you. Otherwise you will always have those feelings; that’s the religious, the Indian way.

If you don’t potlatch on your loved one, then something will bother you all the time. So when they do that, pay those who take care of the grave, who worked for loved ones, they give them gifts, give them food and things like that, they don’t feel bad anymore. They’re happy. Their loved ones gone, that’s the way they feel. That’s why the potlatch, it really means to potlatch over our loved ones.

– Glenda Ewan, 12.9.1987 OTHB interview

For some people, giving away gifts is a cleansing experience. As one man from Mentasta said:

“When some man lost their daughter or son, they feel it all their life. If they don’t do anything for the grave it’s just like they’re lost. They can’t get back their strength. If they put up a potlatch then they come up and have power just like before. [So] they feel like before again. If they don’t give away, it will bother them all of the time. That’s why the potlatch.”

– Mentasta elder, quoted in Strong 1972:31

Memorial potlatches are often held years after a funeral and are a formal and public payment of the mourner’s debt to those people who participated in the funeral and attended the potlatch. Bacille George made that clear when he said, “… somebody bury your relation, you got to pay.”

If he don’t pay me, he has to potlatch me some time. I don’t work for nothing. His other relations help him to give a potlatch. Just like get good record that way. Really law, old time. If he don’t pay, he’s no man, don’t own nothing, no good, stingy.

– Bacille and Nancy George, 8.22.1960 del/mc

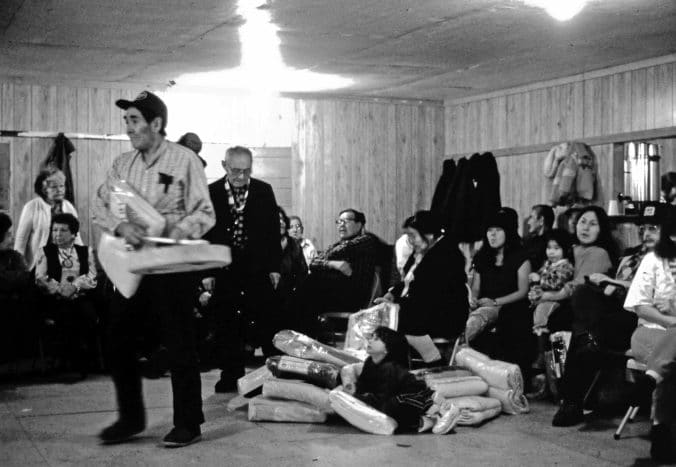

As in the past, the size of a memorial potlatch today often depends on the age and social status of the individual for whom the potlatch is given and the wealth of the hosts. A major potlatch given by a wealthy man or woman can include guests from all of the Ahtna communities as well as people from upper Tanana River villages and Anchorage and Fairbanks.

Memorial potlatches are passionate events in which overwhelming grief is transformed into joy. As the potlatch begins, the mourners are allowed to express their grief by crying, dancing and singing sorry songs made specially to eulogize the dead. After a certain amount of time, the mourners are drawn back from the abyss of desolation by joyous dancing and singing that emphasizes life over death. Finally, the hosts expel their grief by distributing gifts that are invested with their sorrow. Through this last act, the mourners symbolically dissolve the corpse and let go of the deceased, ending the period of public mourning.

As the hosts dissolve their grief, they gain enormous prestige for their lavish display of hospitality, fulfilling their obligation and demonstrating respect for members of the opposite moiety who are their father’s relatives.

Potlatch – Have big time, big dance. Then we give it all away. We got nothing. We broke. You go home. Then you got good name, big name – “rich woman.” Everybody who gives a potlatch is rich. Like put in the bank, just for name is why we potlatch. Who don’t potlatch got no name. If you have a million dollars you are not rich if you don’t potlatch. You don’t count, don’t mean nothing to nobody. If he do potlatch, that’s a big man, big man coming.

Yes women too. Same way – “rich woman.” They got like records [for giving potlatches] – big name just for the name, big name. Big shot.

– Bacille George, 8.28.1958 del/mc